09/05/2013

Ovumboros

14:36 Publié dans Blog, Symbolisme | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : ovumboros, emily fundis

08/05/2013

Мария Архипова (Аркона) и Веданъ Колодъ

Masha (Arkona) & Vedan Kolod

Vedan Kolod > http://vedan-kolod.ru/e_index1.htm

http://www.myspace.com/vedankolod

Arkona > http://www.arkona-russia.com/en/enews/

http://www.myspace.com/arkonarussia

Peut-être bien que "les blancs ne savent pas sauter" ?

( Et franchement, on s'en contrefout ! )

Mais ce qu'il y a de sûr par contre… c'est que les Russes, eux, savent chanter !

11:44 Publié dans Blog, Musique, Svarga - Slava | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : Мария Архипова, Аркона, Веданъ Колодъ, masha, arkona, vedan kolod, vidéo, slava

04/05/2013

WARDRUNA - Yggdrasil

10:32 Publié dans Blog, Musique, Yggdrasil | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : wardruna, yggdrasil, runes, runologie, paganisme, spiritualité, vidéo

03/05/2013

Jeff Hanneman - 2 mai 2013

Jeff Hanneman

( 31 janvier 1964 / 2 mai 2013 )

12:10 Publié dans Blog, Européens d'Outre-europe, In memoriam, Musique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : jeff hanneman, slayer, in memoriam

01/05/2013

And Thus In Nineveh

And Thus In Nineveh

Aye ! I am a poet and upon my tomb

Shall maidens scatter rose leaves

And men myrtles, ere the night

Slays day with her dark sword.

Lo ! this thing is not mine

Nor thine to hinder,

For the custom is full old,

And here in Nineveh have I beheld

Many a singer pass and take his place

In those dim halls where no man troubleth

His sleep or song.

And many a one hath sung his songs

More craftily, more subtle-souled than I ;

And many a one now doth surpass

My wave-worn beauty with his wind of flowers,

Yet am I poet, and upon my tomb

Shall all men scatter rose leaves

Ere the night slay light

With her blue sword.

It is not, Raana, that my song rings highest

Or more sweet in tone than any, but that I

Am here a Poet, that doth drink of life

As lesser men drink wine.

Ezra Pound

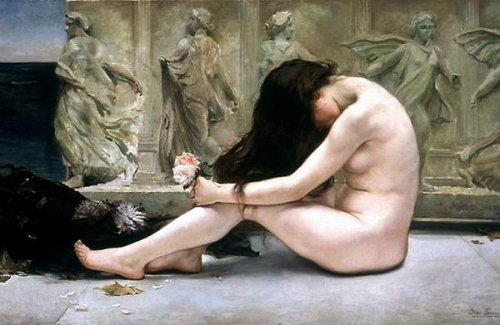

La tombe du poète, par Pedro Sáenz Sáenz (1863-1927)

21:53 Publié dans Blog, Européens d'Outre-europe, Poésie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : ezra pound, poésie

30/04/2013

Vie d'un païen / Jacques Perry

– Tu cours partout, tu aides tout le monde, mais si tu restes une demi-heure à droite, une demi-heure à gauche, jamais on ne te paiera ! C’était vrai. On ne me payait pas ; mais chez les Colas, à la saison des fruits, je prenais tout ce que je voulais. Je ne demandais pas ; on ne me disait pas : « prends » ; cela paraissait naturel. Chez Lorne, je lisais les livres. Chez Ladeuil, je m’amusais à fabriquer des piquets de fer pour attacher les vaches à Colas. Boubée, le pharmacien, m’envoyait porter un flacon chez un médecin ou chercher une bonbonne à la gare et je plongeais la main dans les bocaux de guimauve et de goudron-tolu.

Je suis sûr que si ma vie ne s’était pas orientée autrement, je serais parvenu à vivre ainsi, toujours libre, toujours utile. J’aurais mangé chez l’un ou chez l’autre, bu des canons un peu partout. Il y a toujours assez de pantalons et de vestes pour tout le monde. La campagne est un vaste réservoir ; je me serais emparé de tous les trop-pleins. Trop de lapins dans cette nichée ? Je les prends ; ma chatte les nourrira, et l’herbe des chemins. Il y a toujours des pommes sur l’arbre, du lait au pis des vaches, des lièvres au collet. A l’automne, la femme du garde-chasse me fait goûter le civet.

Je sais que je passe pour un vieux con quand je vante la vie d’autrefois mais on n’a aucune idée de la tranquillité de ces petits pays. On n’aimait pas donner de l’argent mais je n’en demandais pas. Il y a du bois dans la forêt ; les braises se conservent sous la cendre. On souffle ; ça repart ; il fait chaud. Les murs sont épais ; la cheminée est grande. Je dors à la nuit et je m’éveille à l’aube. Quand il pleut, on épluche les châtaignes, on égrène le maïs ou on dort dans le foin.

J’aide le tonnelier et j’emmène un vieux fût de cinquante-cinq ; je vendange chez l’Astruc et je remplis mon fût. En voilà pour un petit mois. Il y a du vin, de l’herbe et du bois pour tout le monde. Je n’aide ni le notaire, ni l’avoué, ni l’avocat, ni l’huissier, ni le médecin qui vivent du malheur des autres. J’aide ceux qui fabriquent et qui font pousser.

Je ne me serais pas marié. Pourquoi faire des mômes ? Ceux des autres sont gentils et tout drôles ; les femmes sont partout. Je les aurais toutes connues. Avec moi, ça n’aurait pas tiré à conséquence et ça aurait fait plaisir.

J’aurais peint quand même, sûrement ; c’est dans ma peau. J’aurais donné les toiles. J’allais dans les châteaux tout aussi bien. Le curé me respectait comme l’oiseau des champs. Vieux, tout le pays m’aidait. J’en suis sûr. Je les ai vus nourrir une vieille chouette impotente et mauvaise. C’est de sortir l’argent qui rend les gens méchants. C’est ça qui a failli me rendre enragé. Vieux et solide comme je suis, j’aurais eu tous les jeunes autour de moi, à me faire raconter toutes mes histoires.

Jacques PERRY : « Vie d’un païen » chez Robert Laffont – 1965.

Léon-Augustin Lhermitte / La paie des moissoneurs - 1882

15:45 Publié dans Blog, Livres - Littérature, Terroir | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : vie d'un païen, terroir, campagne, jacques perry

30 avril 1863 / Camerone

15:44 Publié dans Blog, Guerriers, Histoire de France, Musique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : camerone, légion étrangère, honneur et fidélité, legio patria nostra, jean-pax méfret

29/04/2013

The Highwayman

The Highwayman

by Alfred Noyes (1880-1958)

The wind was a torrent of darkness among the gusty trees,

The moon was a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas,

The road was a ribbon of moonlight over the purple moor,

And the highwayman came riding—

Riding—riding—

The highwayman came riding, up to the old inn-door.

He'd a French cocked-hat on his forehead, a bunch of lace at his chin,

A coat of the claret velvet, and breeches of brown doe-skin;

They fitted with never a wrinkle: his boots were up to the thigh.

And he rode with a jeweled twinkle,

His pistol butts a-twinkle,

His rapier hilt a-twinkle, under the jeweled sky.

Over the cobbles he clattered and clashed in the dark inn-yard,

He tapped with his whip on the shutters, but all was locked and barred;

He whistled a tune to the window, and who should be waiting there

But the landlord's black-eyed daughter,

Bess, the landlord's daughter,

Plaiting a dark red love-knot into her long black hair.

And dark in the dark old inn-yard a stable-wicket creaked

Where Tim the ostler listened; his face was white and peaked;

His eyes were hollows of madness, his hair like moldy hay,

But he loved the landlord's daughter,

The landlord's red-lipped daughter,

Dumb as a dog he listened, and he heard the robber say—

"One kiss, my bonny sweetheart, I'm after a prize tonight,

But I shall be back with the yellow gold before the morning light;

Yet, if they press me sharply, and harry me through the day,

Then look for me by moonlight,

Watch for me by moonlight,

I'll come to thee by moonlight, though hell should bar the way."

He rose upright in the stirrups; he scarce could reach her hand,

But she loosened her hair in the casement. His face burnt like a brand

As the black cascade of perfume came tumbling over his breast;

And he kissed its waves in the moonlight,

(Oh, sweet black waves in the moonlight!)

Then he tugged at his rein in the moonlight, and galloped away to the West.

He did not come in the dawning; he did not come at noon;

And out of the tawny sunset, before the rise of the moon,

When the road was a gypsy's ribbon, looping the purple moor,

A red-coat troop came marching—

Marching—marching—

King George's men came marching, up to the old inn-door.

They said no word to the landlord, they drank his ale instead,

But they gagged his daughter and bound her to the foot of her narrow bed;

Two of them knelt at her casement, with muskets at their side.

There was death at every window;

And hell at one dark window;

For Bess could see, through her casement, the road that he would ride.

They had tied her up to attention, with many a sniggering jest.

They had bound a musket beside her, with the barrel beneath her breast.

"Now keep good watch!" and they kissed her. She heard the doomed man say—

Look for me by moonlight;

Watch for me by moonlight;

I'll come to thee by moonlight, though hell should bar the way!

She twisted her hands behind her; but all the knots held good.

She writhed her hands till her fingers were wet with sweat or blood.

They stretched and strained in the darkness, and the hours crawled by like years,

Till, now, on the stroke of midnight,

Cold, on the stroke of midnight,

The tip of one finger touched it! The trigger at least was hers!

The tip of one finger touched it. She strove no more for the rest.

Up, she stood up to attention, with the muzzle beneath her breast.

She would not risk their hearing; she would not strive again;

For the road lay bare in the moonlight;

Blank and bare in the moonlight;

And the blood of her veins, in the moonlight, throbbed to her love's refrain.

Tlot-tlot; tlot-tlot! Had they heard it? The horse-hoofs ringing clear;

Tlot-tlot, tlot-tlot, in the distance? Were they deaf that they did not hear?

Down the ribbon of moonlight, over the brow of the hill,

The highwayman came riding,

Riding, riding!

The red-coats looked to their priming! She stood up, straight and still!

Tlot-tlot, in the frosty silence! Tlot-tlot, in the echoing night!

Nearer he came and nearer! Her face was like a light!

Her eyes grew wide for a moment; she drew one last deep breath,

Then her finger moved in the moonlight,

Her musket shattered the moonlight,

Shattered her breast in the moonlight and warned him—with her death.

He turned; he spurred to the west; he did not know who stood

Bowed, with her head o'er the musket, drenched with her own red blood.

Not till the dawn he heard it, his face grew gray to hear

How Bess, the landlord's daughter,

The landlord's black-eyed daughter,

Had watched for her love in the moonlight, and died in the darkness there.

Back, he spurred like a madman, shouting a curse to the sky,

With the white road smoking behind him and his rapier brandished high!

Blood-red were his spurs in the golden noon; wine-red was his velvet coat,

When they shot him down on the highway,

Down like a dog on the highway,

And he lay in his blood on the highway, with the bunch of lace at his throat.

And still of a winter's night, they say, when the wind is in the trees,

When the moon is a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas,

When the road is a ribbon of moonlight over the purple moor,

A highwayman comes riding—

Riding—riding—

A highwayman comes riding, up to the old inn-door.

Over the cobbles he clatters and clangs in the dark inn-yard;

He taps with his whip on the shutters, but all is locked and barred;

He whistles a tune to the window, and who should be waiting there

But the landlord's black-eyed daughter,

Bess, the landlord's daughter,

Plaiting a dark red love-knot into her long black hair.

17:45 Publié dans Blog, Musique, Poésie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : loreena mckennitt, the highwayman, alfred noyes

26/04/2013

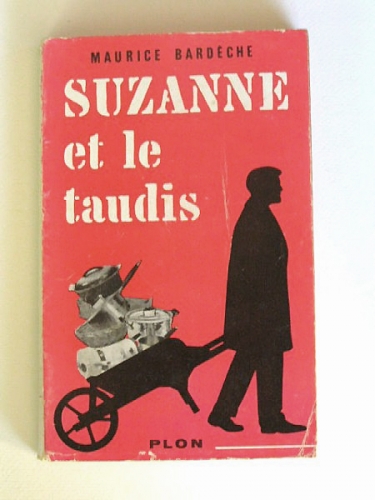

Suzanne et le taudis...

« Maurice Bardèche était le beau-frère de Robert Brasillach. Il entra dans la Collaboration après la Libération, ce qui était pousser loin l’anticonformisme. Il fallait beaucoup de cran ou d’étourderie à un intellectuel français pour devenir fasciste en 1945. Bardèche raconte, dans « Suzanne et le taudis », les difficultés matérielles qui suivirent son engagement dans une cause résolument perdue. Chassé de l’Université, des journaux, et en fait d’un peu partout, Maurice se trouve bien en peine d’assurer une vie décente à sa femme et à ses enfants, et c’est avec une bonne humeur incassable qu’il leur offre une existence indécente. Le premier logement des Bardèche à Montmartre est surnommé le Taudis. Suzanne, bourgeoise de province, en prend son parti, mais ce n’est pas le même que celui de Maurice, c’est celui de la vie quotidienne, de l’amour des enfants, de l’entente avec les voisins et de l’affection des commerçants. Cette belle jeune femme fantasque charme tout le quartier, y compris quand son mari se retrouve en prison pour avoir, dans un livre resté célèbre chez les bouquinistes pour son prix prohibitif, critiqué le procès de Nuremberg. C’est bizarrement chez les communistes que Suzanne Bardèche, ex-Brasillach, trouve le plus de compréhension et de secours. Le fasciste et le communiste sont des proscrits naturels, ontologiques; ils se comprennent et s’entraident comme le bourgeois de gauche et le bourgeois de droite, leurs homologues en meilleur santé physique, morale et financière.

« Maurice Bardèche était le beau-frère de Robert Brasillach. Il entra dans la Collaboration après la Libération, ce qui était pousser loin l’anticonformisme. Il fallait beaucoup de cran ou d’étourderie à un intellectuel français pour devenir fasciste en 1945. Bardèche raconte, dans « Suzanne et le taudis », les difficultés matérielles qui suivirent son engagement dans une cause résolument perdue. Chassé de l’Université, des journaux, et en fait d’un peu partout, Maurice se trouve bien en peine d’assurer une vie décente à sa femme et à ses enfants, et c’est avec une bonne humeur incassable qu’il leur offre une existence indécente. Le premier logement des Bardèche à Montmartre est surnommé le Taudis. Suzanne, bourgeoise de province, en prend son parti, mais ce n’est pas le même que celui de Maurice, c’est celui de la vie quotidienne, de l’amour des enfants, de l’entente avec les voisins et de l’affection des commerçants. Cette belle jeune femme fantasque charme tout le quartier, y compris quand son mari se retrouve en prison pour avoir, dans un livre resté célèbre chez les bouquinistes pour son prix prohibitif, critiqué le procès de Nuremberg. C’est bizarrement chez les communistes que Suzanne Bardèche, ex-Brasillach, trouve le plus de compréhension et de secours. Le fasciste et le communiste sont des proscrits naturels, ontologiques; ils se comprennent et s’entraident comme le bourgeois de gauche et le bourgeois de droite, leurs homologues en meilleur santé physique, morale et financière.

Bardèche excelle dans la peinture de la vie de famille d’extrême droite. Règne du désordre total. Il décrit, avec une ironie conviviale, les bonnes bretonnes et les départs en vacances au Canet. Raconte comment une famille de sept personnes peuvent passer une nuit exquise dans un wagon de troisième classe. Obligés sommes-nous de le croire sur parole, puisqu’il n’y a plus de familles de sept personnes ni de troisième classe ! Scènes inoubliables où le jeune Antoine Blondin vient porter de l’eau chez les Bardèche pour le bain du dernier-né, où Mme Otto Abetz vient discuter avec Maurice du moyen de sortir son mari de prison, où Marcel Aymé s’installe dans le salon des Bardèche dans le seul but de se taire pendant plusieurs heures. Les années 60 n’ont pas été que celles de Sartre et Camus, grandes consciences et vastes talents largement commentés par les médias de l’époque. Il y eut aussi, dans les petits appartements des quartiers excentrés, le bal des écrivains maudits. Discussions sans fin ni moyens. Soirées d’opprimés avec mauvais vin rouge et mauvaise conscience. « Suzanne et le taudis », qui ne sera pas réédité – par Plon, son éditeur originel, ou qui que ce soit d’autre – avant 2500 ou même 3000, est le récit irremplaçable d’une époque oubliée, condamnée. Je ne prêterai mon exemplaire à personne. Débrouillez-vous ! »

Repris de « Bardèche, maman, la bonne et moi », in « Solderie »,

Patrick Besson Mille et une nuits, 2004.

11:02 Publié dans Blog, Livres - Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : maurice bardèche, suzanne bardèche, suzanne et le taudis, patrick besson

24/04/2013

Eivør Pálsdóttir - Brostnar Borgir

22:55 Publié dans Blog, Musique, Yggdrasil | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : eivør pálsdóttir