29/05/2013

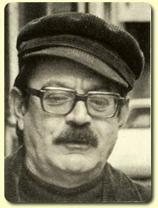

Bernard Clavel, 29 mai 1923.

Bernard CLAVEL

Né le 29 mai 1923 à Lons-le-Saunier et mort le 5 octobre 2010 à La Motte-Servolex.

Cliquez sur le lien ci-dessous pour découvrir quelques livres

de Bernard Clavel disponibles via notre espace boutique.

> http://fierteseuropeennes.hautetfort.com/archive/2012/09/28/bernard-clavel.html

Et/ou sur celui-ci… pour vous rendre sur le site officiel !

> http://www.bernard-clavel.com/

--------------------------

Et puis… http://lacrypteduchatroux.hautetfort.com/archive/2012/09/...

16:04 Publié dans Blog, Boutique, Histoire de France, Livres - Littérature, Terroir | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : bernard clavel, livres, histoire de france, franche-comté, jura, terroir

22/05/2013

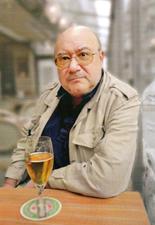

Dominique Venner / 16 avril 1935 - 21 mai 2013

Dominique Venner / 16 avril 1935 - 21 mai 2013

Avant de se donner la mort, hier, mardi 21 mai à 16 heures, devant l’autel de la cathédrale de Notre-Dame de Paris, l’écrivain et historien Dominique Venner a fait parvenir une lettre à ses amis.

La dernière lettre de Dominique Venner.

Je suis sain de corps et d’esprit, et suis comblé d’amour par ma femme et mes enfants. J’aime la vie et n’attend rien au-delà, sinon la perpétuation de ma race et de mon esprit. Pourtant, au soir de cette vie, devant des périls immenses pour ma patrie française et européenne, je me sens le devoir d’agir tant que j’en ai encore la force. Je crois nécessaire de me sacrifier pour rompre la léthargie qui nous accable. J’offre ce qui me reste de vie dans une intention de protestation et de fondation. Je choisis un lieu hautement symbolique, la cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris que je respecte et admire, elle qui fut édifiée par le génie de mes aïeux sur des lieux de cultes plus anciens, rappelant nos origines immémoriales.

Alors que tant d’hommes se font les esclaves de leur vie, mon geste incarne une éthique de la volonté. Je me donne la mort afin de réveiller les consciences assoupies. Je m’insurge contre la fatalité. Je m’insurge contre les poisons de l’âme et contre les désirs individuels envahissants qui détruisent nos ancrages identitaires et notamment la famille, socle intime de notre civilisation multimillénaire. Alors que je défends l’identité de tous les peuples chez eux, je m’insurge aussi contre le crime visant au remplacement de nos populations.

Le discours dominant ne pouvant sortir de ses ambiguïtés toxiques, il appartient aux Européens d’en tirer les conséquences. À défaut de posséder une religion identitaire à laquelle nous amarrer, nous avons en partage depuis Homère une mémoire propre, dépôt de toutes les valeurs sur lesquelles refonder notre future renaissance en rupture avec la métaphysique de l’illimité, source néfaste de toutes les dérives modernes.

Je demande pardon par avance à tous ceux que ma mort fera souffrir, et d’abord à ma femme, à mes enfants et petits-enfants, ainsi qu’à mes amis et fidèles. Mais, une fois estompé le choc de la douleur, je ne doute pas que les uns et les autres comprendront le sens de mon geste et transcenderont leur peine en fierté. Je souhaite que ceux-là se concertent pour durer. Ils trouveront dans mes écrits récents la préfiguration et l’explication de mon geste.

Dominique Venner.

Dominique Venner sera à jamais présent à nos côtés.

>>> http://lecheminsouslesbuis.wordpress.com/

-----------------------------------------------------

Blog de Dominique Venner - 21 mai 2013.

Les manifestants du 26 mai auront raison de crier leur impatience et leur colère. Une loi infâme, une fois votée, peut toujours être abrogée.

Je viens d’écouter un blogueur algérien : « De tout façon, disait-il, dans quinze ans les islamistes seront au pouvoir en France et il supprimeront cette loi ». Non pour nous faire plaisir, on s’en doute, mais parce qu’elle est contraire à la charia (loi islamique).

C’est bien le seul point commun, superficiellement, entre la tradition européenne (qui respecte la femme) et l’islam (qui ne la respecte pas). Mais l’affirmation péremptoire de cet Algérien fait froid dans le dos. Ses conséquences serraient autrement géantes et catastrophiques que la détestable loi Taubira.

Il faut bien voir qu’une France tombée au pouvoir des islamistes fait partie des probabilités. Depuis 40 ans, les politiciens et gouvernements de tous les partis (sauf le FN), ainsi que le patronat et l’Église, y ont travaillé activement, en accélérant par tous les moyens l’immigration afro-maghrébine.

Depuis longtemps, de grands écrivains ont sonné l’alarme, à commencer par Jean Raspail dans son prophétique Camp des Saints (Robert Laffont), dont la nouvelle édition connait des tirages record.

Les manifestants du 26 mai ne peuvent ignorer cette réalité. Leur combat ne peut se limiter au refus du mariage gay. Le « grand remplacement » de population de la France et de l’Europe, dénoncé par l’écrivain Renaud Camus, est un péril autrement catastrophique pour l’avenir.

Il ne suffira pas d’organiser de gentilles manifestations de rue pour l’empêcher. C’est à une véritable « réforme intellectuelle et morale », comme disait Renan, qu’il faudrait d’abord procéder. Elle devrait permettre une reconquête de la mémoire identitaire française et européenne, dont le besoin n’est pas encore nettement perçu.

Il faudra certainement des gestes nouveaux, spectaculaires et symboliques pour ébranler les somnolences, secouer les consciences anesthésiées et réveiller la mémoire de nos origines. Nous entrons dans un temps où les paroles doivent être authentifiées par des actes.

Il faudrait nous souvenir aussi, comme l’a génialement formulé Heidegger (Être et Temps) que l’essence de l’homme est dans son existence et non dans un « autre monde ». C’est ici et maintenant que se joue notre destin jusqu’à la dernière seconde. Et cette seconde ultime a autant d’importance que le reste d’une vie. C’est pourquoi il faut être soi-même jusqu’au dernier instant. C’est en décidant soi-même, en voulant vraiment son destin que l’on est vainqueur du néant. Et il n’y a pas d’échappatoire à cette exigence puisque nous n’avons que cette vie dans laquelle il nous appartient d’être entièrement nous-mêmes ou de n’être rien.

Dominique Venner

( http://www.dominiquevenner.fr/2013/05/la-manif-du-26-mai-et-heidegger/ )

« Quand j’étais gamin, petit Parisien élevé au gaz d’éclairage et au temps des restrictions, mon père m’avait envoyé prendre l’air à la campagne, aux soins d’un vieux couple. Lui était jardinier, il bricolait çà et là, entre les plants de carottes et les rangs de bégonias. Le bonhomme était doux et tendre, même avec ses ennemies les limaces. Devant sa femme, jamais il n’ouvrait la bouche, à croire qu’elle lui avait coupé la langue et peut-être autre chose. Il n’avait même pas droit aux copains c’est-à-dire au bistrot. J’étais son confident, le seul, je crois, qui eut jamais ouvert le cœur à sa chanson. Il me racontait le temps lointain quand il avait été un homme. Cela avait duré quatre années terribles et prodigieuses, de 1914 à 1918. Il était peut-être un peu simple d’esprit mais son œil était affûté et son bras ne tremblait pas. Un officier avait repéré les aptitudes du bougre et fait de lui un tireur d’élite, un privilégié. Armé de son Lebel, li cartonnait ceux d’en face avec ardeur et précision, sans haine ni remords. Libre de sa cible et de son temps, exempté de la plupart des corvées, il était devenu un personnage ; Il tirait les porteurs d’épaulettes et de galons en feldgrau. Il me cita des chiffres incroyables qui avaient sans doute gonflé dans sa petite tête radoteuse en trente ans de remachouillis solitaires. Avec lui j’ai découvert cette vérité énorme que la vie d’un homme, ce ne sont pas les années misérables qui se traînent du berceau à la tombe, mais quelques rares éclairs fulgurants ; Les seuls qui méritent le nom de vie. Ceux que l’on doit à la guerre, l’amour, l’aventure, l’extase mystique ou la création. A lui, la guerre, généreusement, avait accordé quatre ans de vie ; Privilège exorbitant au regard de tous les bipèdes mis au tombeau sans jamais avoir vécu. »

« Mes choix profonds n’étaient pas d’ordre intellectuel mais esthétiques. L’important pour moi n’était pas la forme de l’Etat –une apparence- mais le type d’homme dominant dans la société. Je préférais une république ou l’on cultivait le souvenir de Sparte à une monarchie vautrée dans le culte de l’argent. Il y avait dans ces simplifications un grand fond de vérité. Je crois toujours aujourd’hui que ce n’est pas la Loi qui est garante de l’homme mais la qualité de l’homme qui garantit la Loi. »

« J’ai rompu avec l’agitation du monde par nécessité intérieure, par besoin de préserver ma liberté, par crainte d’altérer ce que je possédais en propre. Mais il existe plus de traverses qu’on ne l’imagine entre l’action et la contemplation. Tout homme qui entreprend de se donner une forme intérieure suivant sa propre norme est un créateur de monde, un veilleur solitaire posté aux frontières de l’espérance et du temps. »

Dominique Venner, Le cœur rebelle. 1994.

( http://hoplite.hautetfort.com/archive/2008/12/07/rebelle.html )

17:43 Publié dans Blog, In memoriam, Livres - Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (2) | Tags : dominique venner, in memoriam

Robert E. Howard & the Heroic

Robert E. Howard & the Heroic

By Jonathan Bowden

Source > http://www.counter-currents.com/

Via : http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com/archive/2013/05/16/r...

Editor’s Note :

The following text is a transcript by John Morgan of a lecture by Jonathan Bowden, "Robert Erwin Howard : Pulpster Extraordinaire", given at the 26th New Right meeting in London on Saturday, April 17, 2010. The audio is available on YouTube [2].

Unfortunately, significant portions of the audio were cut off at the beginning of the second and third segments on YouTube. For the purposes of publishing this essay in the Pulp Fascism [3] collection, I also removed some 2,300 words of digressive material. If anyone has access to a complete copy of the lecture, please contact me. Also, if you have any corrections or if you can gloss the passages marked as unintelligible, please contact me at editor@counter-currents.com [4] or simply post them as comments below. If and when a complete transcript can be assembled, we will publish it here as well.

I’ll be talking about Robert Ervin Howard. A while back, I had a talk about H. P. Lovecraft, Aryan mystic, and he was one of a triumvirate of writers who wrote for a fantasy magazine called Weird Tales, a pulp magazine ; they were incredibly cheaply produced magazines in the 1930s, with quite good art, graphic sort of art, printed on cheap bulk newsprint paper which was very acidic and fell apart very quickly. And yet three writers, Clark Ashton Smith, Robert Ervin Howard, and Howard Phillips Lovecraft have survived and been inducted into literature. I saw in my local library that Penguin Classics, or Modern Classics, the ones with the grey covers, now include Robert Erwin Howard’s Heroes in the Wind, from Kull to Conan : The Best of Robert E. Howard as a book. Penguin Classics, you see ? So it begins as a pulp, and a hundred years later it’s redesignated as literature.

Howard is a very interesting figure. He only lived 30 years. He was born in 1906 and shot himself with a revolver in the head in his car, outside his home, when he was 30 years of age. We’ll get on to that afterwards. He wrote 160 stories, and the interesting thing about these stories is that they are pre-civilized in their settings, they’re barbaric, they’re ultra-masculine stories, and they deal with many themes which have been so disprivileged from much of mainstream liberal humanist culture that they no longer exist.

Howard had a range of heroes and wrote in most popular genres. He wrote to make money, but he began as a poet, and a poetic and sort of Saturnalian disposition influenced his work and his friendship, by correspondence, with Lovecraft, and to a lesser extent, Clark Ashton Smith, throughout his life. He was of Irish descent, and he was born in a town which became a boom town in the oil booms of the early 20th century in Texas. For those of you who don’t know, Texas is enormous. England fits into Texas twelve times, and Britain, eight times. He was born in Peaster, Texas, and spent some of his early life in a town called Brownwood, a quintessentially small-town American, which is the experience of most white Americans through the settlement of Western civilization in North America. The state capital, of course, is Austin, and you have the big cities like Houston, Dallas, and Galveston.

Now, Howard hated the oil booms, and what happened. When the oil boom happened to Cross Plains, a town of about 1,200 with a mayor and so on, morphed into a large, sprawling, lawless place of about 10,000. An enormous number of prospectors and drillers and criminals and people seeking easy money, all heavily armed of course, came in to Cross Plains. The town burst out beyond its limits in all directions. Oil was discovered everywhere. Fortunes were made, and fortunes were lost.

At the time he was born, lynchings were still in vogue right across the South and the ex-Confederate states. Everyone displayed and carried weapons openly. Sometimes the Rangers, as they were called, a man alone in the sun with a rifle, was basically all you had of semi-ordered civilization. People don’t realize how, if you like, wild and open certain parts of the United States were, certainly until the 1860s, 1870s.

The psychological experience of an intuitive and sympathetic and radically imaginative young man like Howard invests the tall Texan story, and stories of prospectors and ranchers and drillers in the oil industry, and Texas Rangers and Marshals and so on, with an added piquancy. His family supported the Confederacy in a previous generation, and he was mildly descended from certain Confederate commanders.

His attitude towards life is expressed in the stories, which is why they survived. The stories are like lucid dreams. You walk straight into them, and the action begins. Most of them were dreams, and in a way, most critics believe Howard’s an oral creator. He’s in the oral, folklorist, and narrative-oriented tradition. He’s a storyteller par excellence. It’s said he wrote at night, and he used to chant the stories to himself, which of course is a very old Northern European and Nordic tradition. It’s the idea of the skald. It’s the idea that things are illuminated to you, and you speak because you hear the voice.

He had a series of masculine heroes beginning with certain Celtic and Pictish/Scotch-Irish heroes such as Bran Mak Morn and so on; Conan, the hero that he’s most associated with, whose name, of course, is abstracted from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s middle name. Howard would take from all sorts of roots, many of which related to heroic, Celtic, Indo-European elements which he imagined to exist in his own past.

He was very influenced by G. K. Chesterton’s dictum at the beginning of the 20th century that myth is the commingling of emotional reality with what is understood to be fact. If you mix together eras and peoples, but you keep the emotional truth of the substance of what we perceive their lives to have been, then you can influence the present and the future. It’s noumenal truth, as Aristotle said 2,000 years ago, the idea that certain things are artistically and emotionally true irrespective of what you think about them factually.

His most famous series of stories, the Conan stories that he wrote pretty much towards the end of his life, were based upon a false yet true/factual world history, the so-called Hyborian Age that he created for himself. Maps of the Hyborian Age have been produced, and they are based upon a realistic sociology, ethnography, geological history, and a coherent view of economics. The country of Aquilonia that Conan ends up conquering at the end of the mythos is partly Britain. The Picts are partly the Scots, of course, covered in woad, barbaric, kept out by a wall, that sort of thing.

War is the dynamic of all of Howard’s fiction, and his attitude towards life was conflict-oriented. His stories are described as ultra-masculine and non-feminist stories. Unkind critics say that they’re Barbara Cartland for men, where all women are beautiful, all men are heroic, where magic works instead of science, and where force decides all social problems, and there is a degree to which the genre which he has founded, called sword and sorcery — of which one supposes J. R. R. Tolkien, an Oxford professor, is the senior representative in the 20th century — is an example of the literary and the heroic in contemporary letters. It’s interesting to notice that the early great texts of the Western civilization, Homer, Beowulf, are deeply heroic, and yet over time, the heroic imprimatur within our language and within our sensibility dips.

It’s said that boys aren’t interested in reading at school, and that 80 to 90% of those who do English literature courses in further educational colleges and universities, the tertiary sector, are women. It’s said that men don’t disprivilege literature, and it’s also said in the West that boys get bullied if they’re regarded, as Howard was when he was younger, as sissies because they read too much, and this sort of thing.

I think one of the problems is that literature that appeals to men is often not the concern of the people who run these sorts of educational establishments. If the sort of people that influenced Howard, people like Noyes, people like Robert W. Service, people like Byron, people like Kipling, people like the heroic imperialist literature of William Henley, who was the basis for Long John Silver in Treasure Island, and was a close friend of Robert Louis Stevenson, a man who could go from bonhomie to murderous rage with a click of your fingers, as Silver does in Treasure Island, of course, because he moves from extreme malevolence to a sort of Cockney paternalism in the same breath. Now, if this literature was normative much further down the social and the educational scale, one would imagine that boys and youngish men would be much more interested in literature as a whole.

Howard essentially sold stories from about the age of 20, certainly 19. He started writing when he was 9, and the interesting thing about him is that his stories are not really derivative. There are connections to enormous writers that were prominent at the time, principally Jack London, but Howard emerged fully-formed and had his own voice from the very beginning.

London’s a very interesting figure, because London’s often been associated, truthfully and yet forcefully, with the extreme Left. Trotsky, of course, wrote an introduction to his famous dystopia of American life called The Iron Heel, and yet London, as George Orwell intimated in one of his essays, was proto-fascistic, and was in many ways a Left nationalist, or even a National Bolshevik, or somebody who would be now described as a Third Positionist. London’s positions were those of socialism from the outside, but also a form of socialism, with and without quotation marks, that was Right-wing rather than Left-wing, and was both national and racial. The interesting thing about London’s discourse is the radicalism of the racialism. [...]

We had at the last meeting, or the meeting before last, a speaker from Croatia called Tomislav Sunić who wrote a book which I edited a long time ago, actually, called Homo Americanus : Child of the Postmodern Age. Among the very important points about that book is his recognition, as a European ex-Catholic in his case, of the Protestant fundamentalist nature of the United States. I think this is a crucial point to understand the United States. The influence of contemporary Jewry in the United States is due to the fact that it’s a Protestant fundamentalist country and many, many Americans really believe in their deep and even subconscious mind that the viewpoint that they are a self-chosen elect to rule by right, by divine imprecation, is so deep in their consciousness, the idea as Pentecostalists sing, that "we are Zion", goes so far down that the difference between their identity and their group specificity and their militant patriotism and that of a small country in the Middle East, and people who didn’t begin to emigrate en masse into the United States until the latter stages of the 19th century, and only really began to have major socioeconomic impact, particularly culturally, in the first quarter to a third of the 20th century makes these things, to my mind, easier to understand.

Now, Protestant fundamentalism doesn’t seem to have scratched Howard very much, and yet one of his heroes is a Puritan called Solomon Kane, and Solomon Kane, who comes between Bran Mak Morn, Kull, and Conan, is in some ways his first major hero. Solomon Kane is very, very interesting because he’s one of these Protestant extremists of the 1620s — well, they’re set before — but that’s when the movement comes to power in the Cromwellian Interregnum in England, and yet stretches way back into the previous century, and yet in a strange way he’s an outsider, even in that movement.

Kane dresses all in black with a little white sort of a bib round his neck. He’s extraordinarily heavily armed, as most of the Puritans were, had a sword on either side, had pistols in the belts, had a knife in the boot, because you were fighting for the Lord, you see ! "I am the flail of the Lord". They had these endless quotes, largely from the Old Testament, but to a degree from elements of the New, which they would roll out on occasions when they had to justify what they were about to do, and that their instincts wanted to do, in a way that nothing could restrain them.

There’s a famous moment in Northern Ireland, when James Callaghan was Northern Irish Secretary under Wilson in the late 1960s, slightly sympathetic to Social Democratic, Catholic nationalism in Northern Ireland, as part of the local movement was then, but in a very moderate way, and then said in a concerned and perplexed way to the Reverend Ian Paisley, who softened a bit as he’s got older, and in turn wanted to be Prime Minister of Northern Ireland before he died, he said to Paisley that, "But we’re all the children of God, Reverend", and Paisley said, "No ! Nooooo !" He said, "We are the children of wrath !"

And that is the attitude of those Puritan extremists, loyal to the Old Testament in many ways. Men of a sort of always implacable fury, and elements of their dictatorship, under Cromwell of course, were increasingly maniacal. The banning of Shakespeare, our greatest writer. When an English national revolutionary movement bans the country’s greatest-ever writer, you do begin to think there’s something slightly wrong, don’t you, no? Similarly, the flogging of actors under the New Model Army in Newcastle for performing Shakespeare, these were the latter stages, these were the Buddhas of Bamiyan moments, weren’t they really, of these English revolutionaries of the 1640s, or what was really going on.

Now, the sort of Puritanism that Howard puts into this character is different, because Howard’s character, Solomon Kane’s a loner, a man who always fights for his own cause, but when he hears those almost voluptuous pagan stirrings in the background, it’s always Christianized, and it’s always put in a Protestant context.

Cromwell once had a phrase : "I disembowel you for Christ’s love". And that’s what he said in the Putney Debates. When the parliamentary side won the Civil War, the whole New Model Army, which of course was a revolutionary army of that time — no brothels, no drinking ; in the Royal army, you went to the back, and there was endless entertainment at the back of the battlefront. With the Puritan armies, there was none of that. You went to the back, and there was no drinking, and there was a chap ranting at you about whether you’d sinned that day.

It was less fun, but at the same time, when they raised their pikes together, not in a higgledy-piggledy way, or one bloke at the back didn’t want to, but they raised them together, as one unit. They would all chant, "God is our strength". Cromwell understood as Shaw said early in the 20th century that a man who has a concept of reality that is metaphysically objectivist, a man who believes in something as absolute truth is worth fifty men. And that’s the type of revolutionary ideology that these people then had.

But at the Putney Debates, there was a debate about how the country should go, and Ireton and the other supreme commanders were there. Under Cromwell they committed regicide of course, they killed the King, so the future of the country was theirs. There was another tendency known as the Levellers, who in some ways of course were retrospectively the first socialists, so-called because they wanted to level down distinctions. There was an even more radical movement called the Diggers that came along later. But Cromwell told Ireton, "Either we hang them or they will hang us". And that’s the Levellers. And at the end of the Putney Debates, the army moves aside, the Cromwellian regime has been established, and the Levellers are hanging on the trees. So Cromwell had got his way.

The importance of Protestantism to the United States, in a complicated way, is the reason why there has never been an extreme Right-wing movement of any great success in the United States, except in a localized way like the Klan to deal with particular circumstances at a particular time. America, you could imagine, is ripe for such a movement, as Australia always has been, and yet there has not been one, not really. Not a national movement. There were figures in the 1930s : there was the Silver Shirt movement ; there were Father Coughlin’s radio broadcasts, which had all sorts of interesting ramifications in American life, as Catholic priest giving the radical Right to essentially a Protestant nation, which of course set up a cultural tension and contradiction in and of itself.

There are also interesting liberal counterparts to this. Most people remember Orson Welles’ treatment of H. G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, when the Martians invade New York, and then he admitted it was a fiction retrospectively, and tens of thousands of ninnies leave New York because they think the Martians are landing. "Gee, they’re up the road !" And they get the pickup truck, and they go. And then they broadcast later that it was all a stunt and it was an artistic show, and people shouldn’t take it literally.

Welles deliberately did that to discredit Coughlin. He said afterwards, "We did it because too many people believed everything that fascist priest was telling them on the radio, so we proved them, don’t believe what you hear that comes out of the radio". And that’s a purely sort of aesthetic response to the impact that sort of thing had.

Yet still movements lie there, Aryan Nations, National Alliance, these sorts of movements, very small, very isolated, geographically and in other ways. National Alliance was quite interesting because it morphed from Youth for George Wallace. That’s how it started, and then it took various transformatory steps until it emerged as a very hard-line group under the late Dr. William Pierce at a later date.

And this culture of extreme Protestantism — which contained elements which are to the Right of almost anything you’ve ever seen, mentally, psychologically, conceptually — seems partly, because, of its extreme individualism, to be incapable of generating radical Right mass movements. Most Americans still adopt a deliberately materialist, liberal humanist and individualist way of looking at life. They divide into two basic political parties that have switched over during the course of the last two centuries. Don’t forget in the 19th century the Republican Party was the party of the nominal Left, and the Democrats were red. The Democrats were conservatives who supported states’ rights — not the right to secede, but certainly the right to own slaves. The party led by a man who’s proud to have ex-slaves in his own family, the present President, would have actually, in a strange sort of way, not been able to join the Democrat Party in the 19th century, and yet the switch around, that you can vote in each other’s primaries, and that "Isn’t everyone a Democrat ? Isn’t everyone a Republican ?", hence the meaninglessness of the names, adds to this sort of feeling that you get in the contemporary United States that all that matters is money and social success. America’s very important, because America, of course, dominates this country now culturally and geopolitically. We can’t almost do anything without them, and all the wars that we’re now dragged into are due to American hegemony.

But the repudiation of parts of American power should never blind ourselves to the cultural excellence of what many white Americans have achieved, both for their group and individually. If you actually look at all the radical Right literature, the alternative side of an isolationist and American nationalist posture, there is some great work there by people like William Gayley Simpson, who wrote an enormous book of over a thousand pages called Which Way Western Man ?Again, without going on a tangent too much, he’s a very interesting man because he’s an ex-Trappist monk. He began as a liberal and an aching humanist whose heart bled for the Third World and who had all the correct sort of UN-specific attitudes, and gradually he changed step by step by step, and he ended up, if not a member then a fellow traveler, of the National Alliance. That is quite a change. That is quite a leap. But it is also true that tens and tens of thousands of educated Western people who are liberal-minded now will have to change their views, will have to begin to change their mindset in this and the coming generation if Western civilization is virtually not to slide off the cliff. [...]

Now, to return to Howard, Howard’s writing, by the end of his sort of period, and don’t forget that he was sort of mature at 22 and dead at 30, he produced 160 stories, 15, 16 volumes basically, and other fragments. There was an unfinished fantasy novel called Almuric, the early Celtic stories, Bran Mak Morn and the others morphed into Solomon Kane. There were associated Westerns and humorous stories. There were some detective stories, but he never particularly liked that genre, although his attitude towards life was hard-boiled. There were also some Crusader stories as well, and some slightly mythological stories about a sort of white man in the East called Gordon, presumably named after the Gordon of Khartoum, but actually an American, and these were the old Borak stories set in Afghanistan, where he goes native and fights along sort of inter-tribal and group-based and clan lines in that context.

Howard’s attitude toward politics is quite complicated and not entirely logical, and primarily emotional. He supported the New Deal because he believed the American economy had collapsed and something needed to be done. He argued strongly with H. P. Lovecraft, he was more of a "reactionary" in these respects, a classical liberal, didn’t like the Roosevelt and the people around him, didn’t like intervention in the market in that sort of Protestant, American way. He felt that you fail commercially, you suffer punishment, because God has chosen that punishment for you. Destiny involves sacrifice.

The irony is that the banks have been saved in the United States by Bush, costing trillions of dollars, but the metaphysic which founded the country would have allowed all of those banks to fail, all of those banks to fail and all those bankers to hang themselves and throw themselves off buildings. That happened in 1929, and then you rebuild quickly, because the pure, American, sort of Randian view is that capitalism is an insatiable animal and vortex of energy, and if people go to pot, if people lose everything they have, if as a trader, an insurance agent I vaguely knew years ago at Lloyd’s, lost all his money in the Names scandal, and goes there on a Sunday and unlocks the door and goes down to the toilets and sits there and drinks Domestos and kills himself and is found by the cleaners, Africans probably, on Monday morning, and his senior partner in Lloyd’s said, "Well, that’s capitalism for you". And that’s it! What goes up goes down! This was the view that founded the United States

And yet the irony is, why have these Western politicians intervened, why have they saved these structures: few collateral damage moments, Lehman Brothers; they’ve charged Goldman Sachs with fraud. Well, that’s a bit late, isn’t it, really ? And yet why have they intervened ? They’ve intervened because of the voting danger. The fact that there are radical parties on the fringe of all Western societies, everyone knows who they are, that people could vote for in a major moment of fiscal/physical/moral/emotional distress, and the whole Western clerisy that’s bought into the contemporary liberal package knows that. Many of these parties are actually quite moderate in relation to the traditions they come out of, but they terrify the present establishment that often sees the more populist ones as just the start of something worse that’s coming behind, see ?

And there’s also a certain guilt there as well, because these people are well aware of what’s happened to Western societies because they’ve been running them for 70 years. This idea it’s all an accident, "I didn’t really mean it," and the turning of Western societies into a sort of version of Brasília, en masse with a tiny, little elite at the top that’s creaming most of the goodies off for themselves.

I’m not an egalitarian in any sense, but it’s interesting to note that this country’s slightly more unequal now than it was in 1910 in terms of 90% of all equity and all capital and all wealth is owned by the top 10%, and the top 2% of that 10%, and yet the society has changed out of all recognition, 1910 to 2010. Most Western people born in the first [unintelligible] part of the 20th century would not believe the transformation of the West just in a lifetime, basically, after they died. And it occurred because of the extraordinary wars, largely amongst ourselves, that we fought in the 20th century that also gave outsider ideologies like Communism their chance to vulture-like pick over the defeat and the carrion corpses of what was left.

The heroic attitude towards man and society that Howard’s work depicts exists virtually nowhere except as play and pleasure in computer games for boys and adolescents, in comic books and so on. The areas of life where that sort of ethos remains, the armed forces, the army, navy, and air force of most contemporary Western societies, particularly their specialist or elite forces, in Britain the Special Air service, the naval equivalent the Special Boat Service, and all of those novels, these Andy McNab sort of novels about the heroic and this sort of thing, which are lapped up by a largely male audience, largely male audience. Other than that, there is not really the imprimatur of the heroic in Western life, the extraordinary demilitarization of Western life, hardly ever see a policeman, hardly ever see soldiers. When do you ever see British forces? And that’s because they’re always outside the country as globalist mercenaries fighting American and Zionist wars all over the world. They’re never seen here, and many of their commanders don’t want them here, either, because they regard parts of British life as so irretrievably decadent that they actually want to keep their troops away from much of what’s happened in relation to the society. There are towns in Berkshire where a lot of the military stay, like Arborfield and these sorts of towns, where it’s quite clear there’s a sort of military zone and there’s a civilian zone. You all know what British towns are like on Friday, Saturday night : no police; they’re all in their vans; they’re all in the station ; they’re at home; they’re filling in forms. They wear yellow bibs when they’re out, but when you want one, you can never see them, can you?

And a lot of our older people are, let’s face it, frightened to go into town and city centers on Thursday, Friday, Saturday, certainly after 6. And why is this happening ? It’s partly happening because the concept that Howard’s fiction deals with, masculinity, has been completely disprivileged, completely demonized and rerouted in contemporary liberal life. Hostility to masculinity, certainly as defined, say, before 1950 is very considerable, and it’s had a very corrosive effect ideologically, aesthetically. Men can have their own pleasures in various zones, which are sort of sneered at and disprivileged, but the centrality of the heroic as a myth for life has largely gone.

The way to explicate something like Howard, as I did with Lovecraft before, is to maybe to concentrate on one of their stories. With H. P. Lovecraft I chose "The Dunwich Horror", and with Howard I would choose "Rogues in the House", which was published in Weird Tales in the early ’30s. One fantasy critic has called it the greatest fantasy story of the 20th century, but that’s just one individual’s opinion. It’s relatively early in the Conan series.

Conan is a northern barbarian, and because everything’s fused together in Howard, he’s got slightly Nordic, Germanic, and slightly Celtic traits. He’s an outsider, but he has a clean code of masculine barbarism. Civilization is always seen as slightly weak-kneed and sybaritic to Howard. And yet at the same time, barbarism has its own inner order.

Now, there are counter-factual and countercultural elements there that will be used by social anthropologists in a totally different context, like Lévi-Strauss and others, in the middle of the 20th century, but Howard means it in a different way.

There’s a Left-wing streak to Howard, as there was to London, a siding with the outsider, with those ruined by capitalism, by tramps. London’s book about the East End is one of the most extraordinary books about mass poverty before George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London and "How the Poor Die", were quite extraordinary works. A poor little hospital in Paris before any sort of socialized medicine, where those who were in the bottom 10%, their corpses were just thrown on the ground! And they died in agony, and they kick you away and put another one on top. This is how the poor die! And Orwell said to this chap in this hospital, "But look at the state they’re in !" And he said, "Well, they gave up slavery. Here’s another batch." This was the attitude then. This is why things like the labor movement, even in the United States in an attenuated way, were created, to correct that imbalance as it’s seen from the bottom.

The far Right, of course, always wanted not the class war of the contemporary Left, but to socialize mass life in a way that preserved the traditions of the civilization of which we’re a part, that brought on what was excellent about the past and yet realized that the 50% of people who own no capital, the 50% of people who are largely excluded from all center-Right parties’ definition of patriotism, are part of the country, are part of the nation, fight the country’s wars for the most part when they’re asked to do so, and therefore have to be within the remit of social consideration in relation to education, health, and other matters.

My explanation for Howard’s support of the New Deal and that type of politics largely is along those sorts of lines. It’s the sort of apolitical chap who likes country and western in a Midwestern state and supports socialized medicine up to a point, as long as it’s not too costly, doesn’t like Obama, and supports our troops, you see. But it’s in a sort of apolitical zone which has got no real knowledge above that. Some of the instincts are right, but the ideological formulation in which that takes place is likely wrong, because even these wars — do you think Iraq was fought for ordinary white Americans ? Do you think Afghanistan has anything to do with ordinary families living in Nebraska or Nevada or Kansas ? None of these wars have anything to do with them at all. Even the Black Muslims have worked out that white gentiles largely are second-class citizens now in the society that they created. But that’s another story, and I’d just like to concentrate on Howard.

This particular story concerns Conan from the outside, Conan as perceived by an aristocrat and fop called Murilo. Howard’s a little bit of a Nordicist. He thinks southern Europeans are a bit foppish in comparison to northern Europeans. There’s a streak of this, and some of the society is seen to be Italy, Corinth, Zamora, but they’re not. But they seem to be Italy.

Well, there’s this Italian city-state that’s run by a corrupt priest called Nabonidus, who’s known as the Red Priest. These myths are set, these stories, mythologically encoded, are set before the beginning of recorded history and after the sinking of Atlantis, possibly a fantasy itself. So he sets them far back enough that he can do whatever he wants with them, but at the same time he can import a large amount of retrospective historical insight.

The interesting thing is the Machiavellianism of the politics of these stories. All of these societies are run extremely ruthlessly and are run completely for the power interests of the people in charge. The nationalities don’t really matter, but they are, if the gloves are off, as marauding and vengeful as their own leaders who they represent at a lower level. Truly Howard believes, with the Roman dictator Sulla, that when the weapons are out, the laws fall silent.

Now, Murilo is a courtier, a relatively corrupt courtier, in this city-state, and Nabonidus comes to him one day at a royal council meeting and gives him a small casket that contains a severed ear. And this is a warning, as it would be if a Renaissance prince in post-Medieval Italy, gave it to a rival, and it’s, "Clear off. Get out of the city-state as quickly as possible. I’m giving you one day". And Murilo wonders what he’s going to do. He can flee, but he’s not a coward, why should he leave his own city ? And in any case he’s got lots of rackets on the go, you know, so he wants an out, and he thinks, "I need to assassinate Nabonidus", who runs the drunken King as a sort of priest/philosopher-king/leader of a native death cult within the city like a puppet master controls his dog.

So he needs a vassal, and he finds it in the prisons of the city where a young, heathen, northern barbarian has been captured and lays there in chains after various escapades and thefts, and this is a young man of 19 called Conan, who’s twice the size of a normal man. All Howard’s heroes are physically enormous, and all incredibly violent, although they all have an honor code of their own which is interesting, particularly towards the end of the story, what you might call an innate code of masculine morality and honor which is part and parcel of natural law.

The Social Darwinian view that was spread throughout mass culture, particularly these types of fictions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, is not entirely true as all prisons and all armies testify, there’s a code of honor and morality even in very extreme male behavior. Rapists are always amongst the most disprivileged in any prison. Men who attack and feed on women, for example, in very all-male and male-concentric cultural spaces are always disprivileged, always disliked, and that’s because of innate feelings about how, in a very traditionalist way, what we call partly a sexist way now, men should treat women, and these things pre-date all modern ideas and are partly innate, and in some ways, because Howard is such an instinctualist, he brings these sorts of forces to the fore.

Now, Nabonidus wants Murilo to leave the city. Murilo hires Conan to murder Nabonidus. Nabonidus is [unintelligible]. Conan is in his cell sucking some beef off a bone, and besides, Nabonidus is an upper-class priest — so why not murder him for money, he’s an adventurer ? — so he decides to go with Murilo on this plot. As always with Howard, a synopsis never does justice to the sort of the lucid dreaming of the story itself. Howard always said that he was there and that Conan was next to him like an old soldier dictating his stories, some of which will be tall stories as well.

Now, Murilo then hears that Conan has been captured because the guard that he bribed to get him out of the prison has been arrested on another offense. Conan’s actually escaped in another way and joins Murilo later. Murilo, desperate, a Borgia without any sort of a family fortune decides to murder Nabonidus himself, so he creeps up to his fortified estate, which is on the edge of town, described in this Gothic way — it’s dark, it’s sepulchral, it’s moonlit, there’s an enormous dog that roams the grounds.

Remember Conan Doyle’s stories ? There’s always this enormous mastiff that the villain has that roams the grounds to bring people down, but Watson shoots on Holmes’ behalf usually at the end. In The Hound of the Baskervilles, which is extraordinarily amusing because the hound is covered with phosphorous to make it glow in the dark when it races after some poor chap who’s looking back, terrified, on a sort of West Country moor, and yet phosphorous is so poisonous that, the dog licks itself all the time, one lick and its dead. But these stories are metaphorical. They’re extreme exercises in the imagination. They’re not concerned with these pettifogging details of which critics make too much.

Now, Murilo creeps into the garden and, horror of horrors, what does he find ? He finds the dead body of the dog, and it looks as though it’s been savagely mauled in a way by something he doesn’t understand, by some weird thing or ape or monster. He then proceeds into the house and finds much of it wrecked. Nabonidus is nowhere to be seen, and one of his servants, Joka, has been murdered.

Suddenly he gets into the inner chamber of Nabonidus’ villa, which is modeled on a Renaissance palace essentially, and he sees the Red Priest, so named because he wears this red cowl, sitting on a throne, made of alabaster, and everything’s heavy and ornamental, a bit like those Cecil B. DeMille films from the ’30s, everything extraordinarily overdone and luxuriant. And he creeps up to Nabonidus to stab him, and the figure turns, and it’s a were-thing, or a monster, something of the imagination. It’s not human at all, simian rather than human. And Murilo faints, and then the story closes.

This story’s in three acts.

Traditionally, like a lot of Western drama, like Dante's Inferno, Purgatory, Paradise, you’ve got this three-pronged triadic element, the thesis, the antitheses, the synthesis at the end. So that’s the first part.

The second part is Murilo awakens in dungeons or interconnected corridors underneath Nabonidus’ house, manse, mansion. He crawls along a corridor and somebody hisses, and it’s Conan. He’s come into the house to murder Nabonidus because Murilo’s going to pay him, and because he’s a member of a cult that he dislikes and so on. Murilo scents his hair, like the young aristocrats of his era, and Conan’s senses are so acute that he detects that with his nostrils, and that’s the reason he doesn’t attack him in the darkness.

They both decide to, they swear loyalty to each other — don’t forget this is an oral culture where bonds and legal sanctions are expressed orally. Howard despised the element of modern life where people say anything they want just to get their own way at any particular time. In pre-modern, say Nordic societies, the oath or something which is given verbally with strength is as binding as any legal document ever could be, even more so.

Conan and Murilo proceed looking for Nabonidus. They come out into the body of the house, which as I said resembles just sort of Renaissance, Florentine palace, and they see Nabonidus stripped, semi-naked and wounded, in a neighboring corridor, and they wonder what has replaced him up inside the house.

And what has happened, as he in a dazed way explains once he returns to full consciousness, is that his servant, who’s this ape that he’s taken from one of the outlying countries in Howard’s imaginary kingdoms, has supplanted him as the master in the house. Howard, to a moderate degree, believed in science, believed in evolution, it was very much almost a cult then, as was eugenics, and Thak as he’s called, this ape-man who wears the red because he’s supplanted the human he wanted to supplant, has thrown his master, Nabonidus, into the pit and has seized control of the house. Thak sits, waiting for them to come out of the pit because there’s a bell underneath there in the pits that they’ve crossed, a trap basically, and he knows humans are down there, and he’s waiting for them.

Nationalists emerge. There’s an interesting political element here, because Nabonidus is a very corrupt ruler and has the King in his thrall, so nationalists of the city-state — you could be a nationalist and of a city-state because it was the unit of civilization essentially, and a country would be city-states federated together. Attempts to assassinate Nabonidus in a way that Murilo wanted to, Thak deals with them. The story fast-forwards in a very filmic way, because Howard is a visualizer. The male brain is visual and always thinks in images. And these sorts of stories are extraordinarily cinematographical in their nature and their forward, pumping lucidity.

Thak senses that they’ve come up from under the ground, and there are interesting pseudo-scientific elements. The Red Priest, Nabonidus is a scientist and a mage and a magician combined. It’s Religion and the Decline of Magic in some ways if you view it academically. He has this construction of mirrors whereby from one room you can reflect light through tubes that contain small mirrors, and it ends up being able to look into another room, so you can actually look round corners, and they can see Thak, and he can see them.

Because he needs to dispose of the bodies of the nationalists who’ve come into the house, Thak disappears for a time, and Conan and the others seize their chance, and they go up. Nabonidus becomes terrified when all the doors are locked and he can’t find the weapons they need to fight against his servant who’s turned against him.

In the end, Conan has to face off against Thak in this quite extraordinarily violent scene. Howard was one of the most brilliant writers of physical force and conflict between men in the 20th century. There’s little doubt about that. It’s so immediate you’re almost there and it is essentially visual. Conan and Thak have this clash-of-the-gods-type of titanic duel with each other, much like a scene from Homer basically, Hector before the walls of Troy. Thak is done down in the end, and Conan, half-dead, is saluted by Murilo.

Nabonidus then tries to betray both of them, and Conan does for him, really, with a stool. He whips up a stool and throws it into his head, and he falls, and all Conan can say is, "His blood is red, not black," because in the slums of the city they said the Red Priest’s blood was black because his heart was black, and Conan’s a barbarian and a literalist, you see. "His blood isn’t black."

There’s an interesting moment when Conan is helped by Murilo because he’s so hurt and wounded in the fight with Thak, and he pushes Murilo aside and says, "A man walks alone. When you can’t stand up it’s time to perish". That’s not an attitude you heard from the Blair government too often, is it ? These are pre-modern attitudes, you see. As somebody on Radio 4 would say now, "But that’s a dangerously exclusionist notion. What about the ill, what about the weak ?" And of course in that type of barbaric morality, the strong look after the weak, but only in an assent of being and natural law which is codified on the basis of the morality of strength. That’s what those sorts of civilizations thought and felt.

And the other interesting thing is that he looks down on Thak, this sort of beast, sort of man that he’s killed, and he says, "I didn’t kill a beast tonight, but a man! And my women will sing of him". And there’s two cultural views of these sorts of things. One is to regard them as remarkable pieces of creative imagination. There is other is to sort of laugh and sneer at them, and think that they represent old-fashioned values that we’ve thankfully gotten rid of, or moved away from.

The stories, with the exception of the Kane stories, are all pre-Christian in the most radical of terms, and yet pre-liberal and liberal secular, which of course in the modern West is what’s replaced Christianity. I would say that contemporary Catholicism is rather like the Protestantism of yesteryear, and Protestantism has become liberalism, and liberalism has morphed, strangely, without the Protestantism that gave it a moral compass, into a form of cultural Marxism, and that’s what we have now.

And yet Howard’s stories are very, very interesting and very dynamic and very much appeal to an imaginative element in certainly a lot of men. The belief in self-definition, the belief in the heroic as a model for life, the belief in strength but with an honor code that saves it from wanton exercise in strength without purpose, and the beliefs that one is part of even a tribe or a community.

In the stories, Conan’s a Cimmerian. He’s from a northern group. He’s always introduced, he’s only got one name, he’s so primal, he doesn’t have any other names. Conan. Like Heathcliff inWuthering Heights, he only had one name. Heathcliff, he doesn’t need any other names. He’s just a force, you see? A force of the female imagination, which is what he is. And in a strange way, the way in which he’s described in that novel by Emily Brontë is very similar to the way Conan’s described, but Conan’s a bit more beefed out, a bit more muscular.

Many films have been made, many TV series have been made, there’s a Conan industry in the 20th century. What Howard would have thought of all that no one knows. He’s there, possibly on a slightly lower tier, but with Tarzan and Doctor Who and James Bond and these other iconic sort of mass popular fantasy figures. Yet in all of them, certainly in this sort of material, there’s a truth to experience, there’s a vividness, there’s a cinematographical and representational reality, and there’s a concern with courage, masculinity, and the heroic which is lacking from most areas of society, and there’s also an honor code, a primitive morality if you like, which goes with it and gives it efficacy and purpose.

The other thing which he differentiates in this type of literature is respect for the enemy. When Terre’Blanche was murdered, I noticed liberals on the BBC giggling and sort of laughing and thinking it was all a jolly joke. These are people who are against the death penalty and believe that murder’s a terrible infraction against human rights, jurisprudence, and all the rest of it. But the sort of cultural space that this work comes out of respects the enemy. Kills the enemy, respects the enemy, which of course is a soldier’s emotion. Many who’ve fought in wars don’t disrespect the enemy. They know what they’re like. British soldiers who’ve fought in the Falklands, American soldiers who’ve fought against Islamist militants, and even some of the militants themselves when they’ve fought against Western warriors, understand the code of the soldier and the code of the warrior on the other side. But many of these men are spiritually, fundamentally similar men in a way, born in other groups.

Men will always fight with each other, and they’re biologically prone to do so. How, in an era of mass weapons of destructive warfare, some existing and others not, that is to be worked through. It is a part of the destiny of the relationship between groups and states. But the hard-wiring that makes men competitive and egotistical and conflict-oriented is ineradicable and irreducible, and modern liberal societies which are based upon the idea of inclusionist love without thought of conflict are sentimental to the point that they will fall apart, bedeviled by their endless contradictions.

And I personally think that if you inculcate yourself, with a bit of irony and estrangement, from some of the elements of the culture of the heroic that certainly subsisted as mainstream cultural fare in our society before 1950, you have a different attitude towards what spews out of the telly every evening, and you have a different attitude towards the sort of culture that you’re living in, and you have a different attitude towards great figures in your own group and even in others, and you have a different attitude towards yourself and the future.

I give you Robert Ervin Howard, 1906 to 1936, a man who walked alone but spoke for an element, not just of America, but what it is to be white, male, Western, and free.

Thank you very much.

Jonathan Bowden

(Transcription by John Morgan).

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2013/05/robert-e-howard-a...

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: http://www.counter-currents.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/0...

[2] YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1ucBGENZjnM

[3] Pulp Fascism: http://www.counter-currents.com/2013/04/forthcoming-from-...

[4] editor@counter-currents.com: mailto:editor@counter-currents.com

15:23 Publié dans Blog, Européens d'Outre-europe, Livres - Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (5) | Tags : robert erwin howard, littérature

30/04/2013

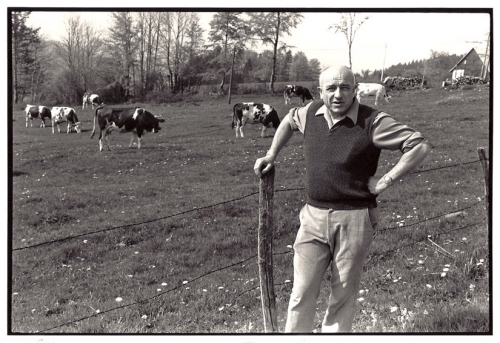

Vie d'un païen / Jacques Perry

– Tu cours partout, tu aides tout le monde, mais si tu restes une demi-heure à droite, une demi-heure à gauche, jamais on ne te paiera ! C’était vrai. On ne me payait pas ; mais chez les Colas, à la saison des fruits, je prenais tout ce que je voulais. Je ne demandais pas ; on ne me disait pas : « prends » ; cela paraissait naturel. Chez Lorne, je lisais les livres. Chez Ladeuil, je m’amusais à fabriquer des piquets de fer pour attacher les vaches à Colas. Boubée, le pharmacien, m’envoyait porter un flacon chez un médecin ou chercher une bonbonne à la gare et je plongeais la main dans les bocaux de guimauve et de goudron-tolu.

Je suis sûr que si ma vie ne s’était pas orientée autrement, je serais parvenu à vivre ainsi, toujours libre, toujours utile. J’aurais mangé chez l’un ou chez l’autre, bu des canons un peu partout. Il y a toujours assez de pantalons et de vestes pour tout le monde. La campagne est un vaste réservoir ; je me serais emparé de tous les trop-pleins. Trop de lapins dans cette nichée ? Je les prends ; ma chatte les nourrira, et l’herbe des chemins. Il y a toujours des pommes sur l’arbre, du lait au pis des vaches, des lièvres au collet. A l’automne, la femme du garde-chasse me fait goûter le civet.

Je sais que je passe pour un vieux con quand je vante la vie d’autrefois mais on n’a aucune idée de la tranquillité de ces petits pays. On n’aimait pas donner de l’argent mais je n’en demandais pas. Il y a du bois dans la forêt ; les braises se conservent sous la cendre. On souffle ; ça repart ; il fait chaud. Les murs sont épais ; la cheminée est grande. Je dors à la nuit et je m’éveille à l’aube. Quand il pleut, on épluche les châtaignes, on égrène le maïs ou on dort dans le foin.

J’aide le tonnelier et j’emmène un vieux fût de cinquante-cinq ; je vendange chez l’Astruc et je remplis mon fût. En voilà pour un petit mois. Il y a du vin, de l’herbe et du bois pour tout le monde. Je n’aide ni le notaire, ni l’avoué, ni l’avocat, ni l’huissier, ni le médecin qui vivent du malheur des autres. J’aide ceux qui fabriquent et qui font pousser.

Je ne me serais pas marié. Pourquoi faire des mômes ? Ceux des autres sont gentils et tout drôles ; les femmes sont partout. Je les aurais toutes connues. Avec moi, ça n’aurait pas tiré à conséquence et ça aurait fait plaisir.

J’aurais peint quand même, sûrement ; c’est dans ma peau. J’aurais donné les toiles. J’allais dans les châteaux tout aussi bien. Le curé me respectait comme l’oiseau des champs. Vieux, tout le pays m’aidait. J’en suis sûr. Je les ai vus nourrir une vieille chouette impotente et mauvaise. C’est de sortir l’argent qui rend les gens méchants. C’est ça qui a failli me rendre enragé. Vieux et solide comme je suis, j’aurais eu tous les jeunes autour de moi, à me faire raconter toutes mes histoires.

Jacques PERRY : « Vie d’un païen » chez Robert Laffont – 1965.

Léon-Augustin Lhermitte / La paie des moissoneurs - 1882

15:45 Publié dans Blog, Livres - Littérature, Terroir | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : vie d'un païen, terroir, campagne, jacques perry

26/04/2013

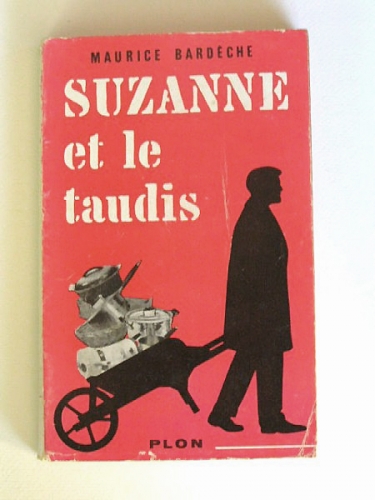

Suzanne et le taudis...

« Maurice Bardèche était le beau-frère de Robert Brasillach. Il entra dans la Collaboration après la Libération, ce qui était pousser loin l’anticonformisme. Il fallait beaucoup de cran ou d’étourderie à un intellectuel français pour devenir fasciste en 1945. Bardèche raconte, dans « Suzanne et le taudis », les difficultés matérielles qui suivirent son engagement dans une cause résolument perdue. Chassé de l’Université, des journaux, et en fait d’un peu partout, Maurice se trouve bien en peine d’assurer une vie décente à sa femme et à ses enfants, et c’est avec une bonne humeur incassable qu’il leur offre une existence indécente. Le premier logement des Bardèche à Montmartre est surnommé le Taudis. Suzanne, bourgeoise de province, en prend son parti, mais ce n’est pas le même que celui de Maurice, c’est celui de la vie quotidienne, de l’amour des enfants, de l’entente avec les voisins et de l’affection des commerçants. Cette belle jeune femme fantasque charme tout le quartier, y compris quand son mari se retrouve en prison pour avoir, dans un livre resté célèbre chez les bouquinistes pour son prix prohibitif, critiqué le procès de Nuremberg. C’est bizarrement chez les communistes que Suzanne Bardèche, ex-Brasillach, trouve le plus de compréhension et de secours. Le fasciste et le communiste sont des proscrits naturels, ontologiques; ils se comprennent et s’entraident comme le bourgeois de gauche et le bourgeois de droite, leurs homologues en meilleur santé physique, morale et financière.

« Maurice Bardèche était le beau-frère de Robert Brasillach. Il entra dans la Collaboration après la Libération, ce qui était pousser loin l’anticonformisme. Il fallait beaucoup de cran ou d’étourderie à un intellectuel français pour devenir fasciste en 1945. Bardèche raconte, dans « Suzanne et le taudis », les difficultés matérielles qui suivirent son engagement dans une cause résolument perdue. Chassé de l’Université, des journaux, et en fait d’un peu partout, Maurice se trouve bien en peine d’assurer une vie décente à sa femme et à ses enfants, et c’est avec une bonne humeur incassable qu’il leur offre une existence indécente. Le premier logement des Bardèche à Montmartre est surnommé le Taudis. Suzanne, bourgeoise de province, en prend son parti, mais ce n’est pas le même que celui de Maurice, c’est celui de la vie quotidienne, de l’amour des enfants, de l’entente avec les voisins et de l’affection des commerçants. Cette belle jeune femme fantasque charme tout le quartier, y compris quand son mari se retrouve en prison pour avoir, dans un livre resté célèbre chez les bouquinistes pour son prix prohibitif, critiqué le procès de Nuremberg. C’est bizarrement chez les communistes que Suzanne Bardèche, ex-Brasillach, trouve le plus de compréhension et de secours. Le fasciste et le communiste sont des proscrits naturels, ontologiques; ils se comprennent et s’entraident comme le bourgeois de gauche et le bourgeois de droite, leurs homologues en meilleur santé physique, morale et financière.

Bardèche excelle dans la peinture de la vie de famille d’extrême droite. Règne du désordre total. Il décrit, avec une ironie conviviale, les bonnes bretonnes et les départs en vacances au Canet. Raconte comment une famille de sept personnes peuvent passer une nuit exquise dans un wagon de troisième classe. Obligés sommes-nous de le croire sur parole, puisqu’il n’y a plus de familles de sept personnes ni de troisième classe ! Scènes inoubliables où le jeune Antoine Blondin vient porter de l’eau chez les Bardèche pour le bain du dernier-né, où Mme Otto Abetz vient discuter avec Maurice du moyen de sortir son mari de prison, où Marcel Aymé s’installe dans le salon des Bardèche dans le seul but de se taire pendant plusieurs heures. Les années 60 n’ont pas été que celles de Sartre et Camus, grandes consciences et vastes talents largement commentés par les médias de l’époque. Il y eut aussi, dans les petits appartements des quartiers excentrés, le bal des écrivains maudits. Discussions sans fin ni moyens. Soirées d’opprimés avec mauvais vin rouge et mauvaise conscience. « Suzanne et le taudis », qui ne sera pas réédité – par Plon, son éditeur originel, ou qui que ce soit d’autre – avant 2500 ou même 3000, est le récit irremplaçable d’une époque oubliée, condamnée. Je ne prêterai mon exemplaire à personne. Débrouillez-vous ! »

Repris de « Bardèche, maman, la bonne et moi », in « Solderie »,

Patrick Besson Mille et une nuits, 2004.

11:02 Publié dans Blog, Livres - Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : maurice bardèche, suzanne bardèche, suzanne et le taudis, patrick besson

10/04/2013

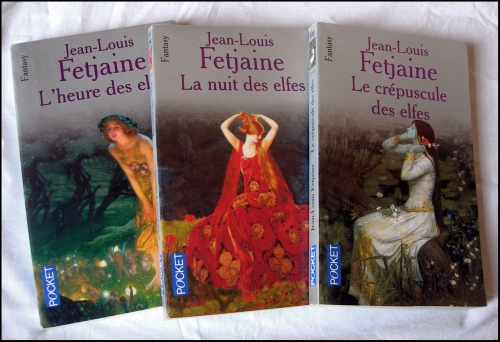

La trilogie des elfes.

Espace boutique :

La trilogie des elfes

Jean-Louis FETJAINE : « Le crépuscule des elfes (1/3) »

« Il y a bien longtemps, avant même Merlin et le Roi Arthur, le monde n'était qu'une sombre forêt de chênes et de hêtres, peuplée d'elfes et de races étranges dont nous avons aujourd'hui perdu jusqu'au souvenir. Dans ces temps anciens, les elfes étaient un peuple puissant et redouté des hommes, des êtres pleins de grâce à la peau d'un bleu très pâle, qui savaient encore maîtriser les forces obscures de la nature. Ce livre est le récit de leurs dernières heures, depuis la rencontre du chevalier Uter et de Lliane, la reine des elfes, dont la beauté fascinait tous ceux qui l'approchaient. L'histoire d'une trahison et de la chute de tout un monde, d'un combat désespéré et d'un amour impossible ».

Dans un Moyen-Âge où le merveilleux côtoie la violence et la cruauté, ce fabuleux roman, nourri par une inépuisable imagination et une grande connaissance du monde médiéval, établit un pont entre l'univers des légendes celtiques, la fantasy et le cycle arthurien.

Presses pocket Fantasy – 2002 – 347 pages – 180 grammes.

Etat = quelques petites marques/traces de manipulation et stockage, mais rien de bien notable, tranche intacte, intérieur propre et sain, exemplaire entre bon et bon+.

Jean-Louis FETJAINE : « La nuit des elfes (2/3) »

Lorsque les hommes ont exterminé les derniers royaumes nains le monde a sombré dans le chaos. Seuls les elfes pourraient s'opposer à eux, mais retranchés dans leurs immenses forêts, ils sont inconscients du danger qui les menace à leur tour.

Pour empêcher le duc Gorlois d'étendre la domination des hommes sur la terre, au nom de Dieu, le druide Merlin s'attache aux pas du chevalier Uter, l'amant de Lliane, la reine des elfes. Investi du pouvoir de Lliane, Uter devient le Pendragon, chef de guerre de tous les peuples libres, et tient désormais entre ses mains le pouvoir de restaurer l'ordre ancien. Mais il lui reste à choisir entre l'amour de deux reines : Lliane, l'inaccessible, réfugiée dans son île d'Avalon ; ou Ygraine, si réelle, si humaine…

Presses pocket Fantasy – 2002 – 265 pages – 150 grammes.

Etat = plats O.K, tranche intacte, l’exemplaire aurait pu être parfait s’il ne souffrait d’un petit choc en bas à droite et surtout d’une trace d’humidité (1,5 cm) visible au haut des 30/35 premières pages. En conséquence de quoi il ne sera donc estampillé que moyen+.

Jean-Louis FETJAINE : « L’heure des elfes (3/3) »

Le monde, partagé entre les nains, les monstres, les elfes et les hommes, a perdu son équilibre depuis que ces derniers se sont approprié la légendaire épée Excalibur. Déchiré entre son épouse, la chrétienne Ygraine, et Lliane, la reine des elfes, le roi Uter a pris la décision de rendre l'épée sacrée et de restaurer ainsi l'ordre ancien.

C'est alors que les monstres envahissent le royaume de Logres et anéantissent leurs adversaires désunis. Affaiblis et terrifiés, les hommes se tournent de nouveau vers les elfes, espérant que le peuple des arbres viendra à leur secours.

Exilée sur l'île d'Avalon avec sa fille Morgane et accompagnée du mystérieux Merlin, la reine Lliane acceptera-t-elle, une fois encore, de tout risquer pour l'amour d'Uter ?

Presses pocket Fantasy – 2002 – 268 pages – 150 grammes.

Etat = quelques petites traces de manipulation et/ou stockage, mais O.K, entre bon et bon+.

Les 3 volumes ( poids total = 480 grammes ) pour :

>>> 5,50 €uros. / Vendus !

Temporairement indisponibles.

Le crépuscule des elfes

Au bord d'une mare, une femme à la peau bleue se coiffe…

C'est sous cette illustration trompeuse, trop sage, que se voile une fantasy aussi épique que tragique de la plus belle plume : celle de Jean-Louis Fetjaine, dont c'est là le premier roman. Un roman sombre et fort, au carrefour de la mythologie celte et de l'épopée arthurienne, dont le ton emprunte à l'Excalibur de John Boorman.

Une arthurienne de plus, me direz-vous ? Oui. Mais la légende arthurienne est un matériau de tout premier choix pour qui veut inscrire sa fantasy dans la veine historique. Cependant, si noble que soit le matériau, il a déjà été forgé sur plus d'un feu (…) On peut écrire de la fantasy sur la base des légendes des indiens Hopi… ce n'est pas un sport pour européens. Par contre légende du roi Arthur est la borne blanche d'un celtisme très en vogue que se partagent la France et le monde anglo-saxon. Sur ce thème là, même une approche originale ne produira pas un roman original. Grand est donc le risque de lasser ; c'est pour l'auteur un défi à relever.

Jean-Louis Fetjaine n'a pas inscrit la tragédie là où on l'attend d'un roman arthurien : dans la mort du roi. D'ailleurs d'Arthur, point. ll a trouvé mieux que la mort d'un homme : celle de tout un univers. A l'instar de Stormbringer – le roman de Moorcock – ce Crépuscule des elfes (comme celui des dieux) illustre la fin d'un monde, une inexorable apocalypse en forme de changement de paradigme.

En ce temps-là, alors qu'Uther était jeune encore, elfes, nains et hommes vivaient en paix : les elfes en harmonie avec la nature, plantes et animaux à qui ils parlaient ; les nains, forgerons nés, maîtrisaient les magies minérales. Et les hommes… l'art cynique de la politique et de l'intrigue, ainsi qu'il apparaîtra au fil du livre (…).

Fetjaine n'a pas oublié d'écrire un roman et non une tragédie. Aussi, si le discursif domine, l'action le soutient et le visuel n'a pas été négligé, au contraire. Son écriture fluide nous fait voir, mieux, sentir un monde froid et liquide, de brume, de bruine, d'eau omniprésente, de boue et de marais glacés, de forêts profondes et détrempées. Il nous fait éprouver ce monde elfique presque monochrome pour mieux empreindre sa tragédie de la nostalgie et du deuil d'un univers. C'est une allégorie du désenchantement du monde ; d'un monde qui ne sera plus jamais le leur – celui des elfes, des nains… Sous la plume de Fetjaine, le bien ne chevauche pas chaussé des mêmes bottes que la chrétienté, incarnée par Pellehun et Gorlois. Il donne à son roman une sensualité liquide et pénétrante qui confère au drame une intensité fluide où les personnages ne prennent corps que pour mieux s'y noyer (…).

Que cet ouvrage ait trouvé place chez un éditeur de littérature générale plutôt que chez un spécialiste du genre tel L'Atalante, Pygmalion ou Rivages, s'explique tant par la qualité de l'écriture que le classicisme du thème. Et si ce crépuscule n'en est pas moins héroïque, avec ce qu'il faut d'épreuves et de combats pour combler tout un chacun, Fetjaine s'est battu avec les armes de la tragédie pour forger son succès. Car, à n'en pas douter, c'en est un.

La fantasy française n'est que bien rarement à pareille fête.

( Jean-Pierre Lion / http://www.noosfere.com/icarus/livres/niourf.asp?numlivre... )

17:05 Publié dans Boutique, Kelts, Livres - Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (2) | Tags : jean-louis fetjaine, la trilogie des elfes, cycle arthurien, merlin, roi arthur, excalibur, fantasy, légendes médiévales

04/04/2013

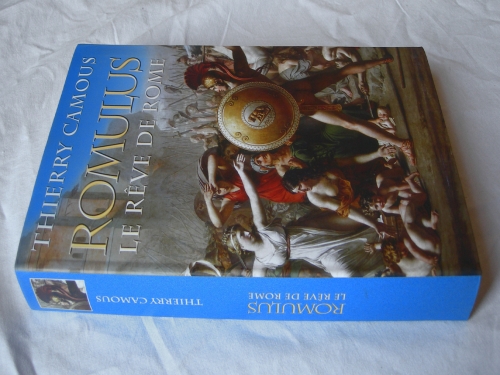

Thierry CAMOUS / Romulus - Le rêve de Rome.

Espace boutique :

Thierry CAMOUS : « Romulus - Le rêve de Rome »

Personnage de légende, Romulus ne nous est connu que grâce à des écrits bien postérieurs au VIIe siècle avant J.-C. où il vécut. Objet de fascination, il reste pour les historiens une véritable énigme et une sorte de tabou scientifique. Or, des découvertes archéologiques récentes prétendant avoir retrouvé le palais royal de Romulus ou la grotte du Lupercal, dans laquelle la louve allaita les jumeaux, permettent d’éclairer d’un jour nouveau la figure du fondateur de Rome. C’est sur l’apport essentiel de ces découvertes, enfin mises à la portée du grand public, que se fonde cette première biographie de Romulus depuis… Plutarque !

En réalité, Romulus condense plusieurs époques, et donc plusieurs personnages. Quatre, pour être exact : l’homme des bois, enfant sauvage abandonné par sa mère, la vestale violée par le dieu Mars, qui tente de reconquérir son trône perdu ; le fondateur, chef de clan qui s’approprie la colline du Palatin en traçant le fameux sillon délimitant l’Urbs, tue son frère Rémus et enlève ses voisines, les Sabines, pour en faire des épouses ; le roi-guerrier, qui organise la cité unifiée, étend sa domination et finit démembré ; et le héros mythique, descendant d’Énée aux origines troyennes.

Cette enquête captivante et érudite nous ouvre les portes d’un monde méconnu, celui de la civilisation des premiers Latins, pâtres belliqueux, de leur métropole mythique au plus profond des bois, Albe-la-Longue, de leur fête sanglante des Lupercales et de leurs terribles batailles contre leurs adversaires étrusques. Au-delà du "portrait en creux" d’un homme, elle nous offre une peinture saisissante de l’Italie primitive, berceau de la civilisation romaine classique. En cela, l’action du roi Romulus, qui se lance dans le Latium à la conquête des voies commerciales, porte en germe un destin impérialiste insoupçonnable alors. Aux frontières du mythe, de l’histoire, de l’archéologie, de l’ethnologie et de l’anthropologie, un essai fascinant sur les origines à la fois tragiques et grandioses de Rome.

Chercheur associé au CNRS, professeur agrégé à Nice et chargé de cours en histoire ancienne à l’université de Sophia-Antipolis et de Guangzhou (Chine), Thierry Camous est spécialiste des origines de Rome (Le roi et le fleuve : Ancus Marcius Rex, aux origines de la puissance romaine, Les Belles Lettres, 2004). Il est également l’auteur de deux synthèses sur les rapports d’altérité entre les civilisations comme moteur de la violence guerrière, qui ont suscité un certain débat : Orients / Occidents, 25 siècles de guerres et La violence de masse dans l'Histoire

(PUF, 2007 et 2010).

Le grand livre du mois – 2010 – 431 pages – 23 x 14 cm – 500 grammes.

Etat = broché, reliure "semi-souple" illustrée par un détail de L’enlèvement des Sabines de David. Tranche intacte, quelques infimes marques de manip’, rien de notable, très bon état.

>>> 6 €uros. / Vendu ! Temporairement indisponible.

(Prix neuf = 25€)

18:14 Publié dans Boutique, Histoire européenne, Livres - Littérature, Rome et Olympie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : thierry camous, romulus, la fondation de rome, romains, étrusques, lupercal, lupercales, sabines

12/03/2013

Passions baroques...

Tout le monde connaît ces avions de papier que les lycéens jettent dans la rangée centrale de la classe quand ils s’ennuient. Le fuselage de l’avion était constitué par l’Esplanade des Invalides. Les ailes faisaient un triangle, dont les pointes étaient le pont de la Concorde, le pont des Invalides et l’extrême avancée, sur la rive droite, de l’avenue Nicolas II.

Qui sait ? Malgré la pierre tendre, le contre-plaqué, les guinguettes du pont Alexandre, l’Exposition des Arts Décoratifs n’était pas forcément un avion pour rire. Les hommes avaient appris à s’envoler. En 1925, rien ne leur paraissait plus merveilleux. L’Exposition n’était peut-être que l’ombre d’un avion qui survolait Paris, avion idéal, bourré d’idées platoniciennes (comme de riches Américaines au visage éthéré), d’archétypes, de catégories, d’équations, de tout cet arsenal qui dominait la Terre.

Voilà pourquoi les animaux du siècle présentaient ces formes géométriques et cet aspect glacial. Longtemps les hommes avaient tout adouci. Ils avaient vécu entre des commodes Louis XV, ventrues comme des pourceaux, et des jeunes femmes de Fragonard au sourire facile. A force de se frotter à leurs tableaux, à leurs vêtements, à force d’ingurgiter des conversations sucrées, ils étaient devenus sages et civilisés.

C’était fini. Le démon de la géométrie l’avait emporté. Les austères lignes droites, en rangs serrés, venaient de conquérir la planète. Ainsi, dans le village de français, régnait la pensée de Leibnitz. Rien ne s’y abandonnait au hasard, puisque tout y était symbole, maille d’un univers bien tissé. On n’avait oublié ni la ferme parfaite, ni l’église idéale, ni le lavoir perfectionné. Seul le tas de fumier était un peu vétuste.

Cependant, le passé subsistait. Il était là sous deux aspects. D’abord celui des vieilles coutumes. Chaque nation avait son pavillon, comme si les hommes de 25 n’avaient pas appartenu à l’acier ou à la T.S.F., avant d’être de Bloomsbury ou de Flandres. Ensuite, par l’assimilation des styles les plus anciens : de Byzance à la Grèce, de l’Afrique aux pays esquimaux, toutes les formes avaient été convoquées, pesées d’un œil sûr, rejetées ou conservées, suivant leur degré de fidélité à la logique. Mais la logique avait toléré certains détails coupables ; ainsi garde-t-on un tableau de famille, une vieille domestique.